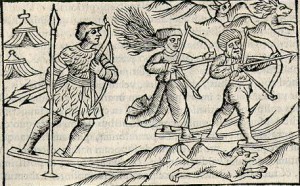

Game Poem 30: The Winter Hunt

It is winter. You are the Siverati, a tribe of people who have lived here since the First Ages. This year, there was a sickness that struck down many of your number. Winter arrived early. Food has been in short supply, and game is scarce this season. There are few of you left. Spring will come in four weeks. In four weeks, the sun will return. If you can survive the winter, the rivers will thaw, and those who remain will have plenty to eat. Still, the game is scarce this winter. To rely on the traditional ways of hunting will mean certain starvation. The tribe’s only recourse is to return to the old ways, to enter the Dream.

To play the Winter Hunt, you will need a fair-sized group of people. Five to eight hunters would be ideal. If there are fewer than five players, each of you should play two hunters apiece. To play, you will need four coins for each hunter. There are a few areas of concern, places that the coins will move in and out of. The first is the tribe’s food supply. Put one coin for each hunter into the food supply. Each of these coins will feed one person for one week The second area is the hunting grounds. Put one coin for every two hunters in the hunting grounds. These first coins will each stand for one small animal. The final area is the draw pile. Put all of the remaining coins in the draw pile. These coins represent only potential.

To begin the first week of hunting, each tribesman will take one coin from the food supply, leaving it empty. Since there is so little game in the hunting grounds, some of the hunters will need to enter the Dream to ask more animals to come to you. Without discussing who will take which role, each player will decide whether their hunter or hunters will hunt or dream by secretly choosing heads or tails on each hunter’s coin. When all have decided, everyone will reveal their coins at the same time, place their coins back into the draw pile, and the Dream will begin.

The dreamers, if any, must decide how many animals they will call upon, and how large they will be. The dreamers must form groups of one, two, or three. Each group of dreamers will describe the game that they wish to summon to the hunting grounds. A single dreamer will call small game, snow rabbits or squirrels. Two dreamers may call something larger, perhaps a wild pig or a deer. Three dreamers will be calling the largest game possible, something the size of an elk, something that will feed many tribesmen well. The groups of dreamers will throw their coins in turn. As long as one dreamer in a group throws a head on their coin, the animal that they have summoned will appear in the hunting grounds. Place the successfully summoned game into the hunting grounds by placing the single coins down, or stacking the coins in twos and threes. Successful groups of dreamers must tell together how the game answered them, and agreed to enter the hunting grounds. Unsuccessful dreamers must speak together to tell how the animal that they asked to come to them refused the call.

Now, if there is game to be had, the hunters will take their turn. Again, the hunters will go out in groups, this time of any size. A single hunter may go into the hunting grounds alone, or all the hunters may go in one large group. In turn, the groups of hunters will tell which game they will seek. Whichever animal they wish to hunt, that group of hunters must throw their coins and reveal enough heads to match the size of the animal. A single hunter may throw one coin to bring back a small animal, or a half-dozen hunters may band together to bring down a three-coin moose – a grand feast for those who hunger! Whatever the size of the band of hunters, if they do not throw the necessary heads to succeed in their hunt, they must each tell the tale of how they failed to bring back food for the tribe. If they are successful, though, each hunter must each tell the story of their skill and bravery as they bring the game back to the tribe’s food stores.

A small one-coin animal will add three coins to the food stores. A medium-sized two-coin animal will add seven coins to the tribe’s stores, and a large three-coin beast will add fifteen coins to the food supply. Clearly the larger game are more difficult to bring back successfully, but the risk may well be worth it. It is possible, of course, that there are no animals in the hunting ground this time. In that case, tell the tale of how the hunters sit around the dying fire, perhaps cursing the Dream for abandoning them, or pleading with it to send them just one small bird to quiet their growling bellies.

At the end of the hunt, the tribe must eat. Each hunter must take one coin from the food supply, if possible. If there are not enough coins to feed every hunter, the tribe must decide in some way who will eat and who will starve. If a hunter starves, they die, leave the game, and must describe their fate. Do they lay in their beds until they are too weak to awaken, or do they walk into the snows, never to be seen again? When a hunter eats, they must tell tale of their meal, how it makes them feel, to eat when others do not. They must tell of the thanks that they give to the animal that surrendered its own life for theirs, and they must tell of the thanks they give to the Dream, which brought them everything that they have.

When the consuming of food and the fates of the dead are dealt with, a new hunt must begin. Each surviving hunter will again decide whether they will hunt or dream, and secretly set and reveal their coin. The coins will be returned to the draw pile, the dreamers will dream, the hunters will hunt, game will be caught and eaten, and some will likely starve to death again. This cycle will take place four times, until winter breaks, and the sun returns to the land of the Siverati. If any of the hunters have survived, they will find fresh game again in the spring, and their tribe will flourish once again. If all of the hunters have starved to death, then all of the Siverati have returned to the Dream once more, perhaps to be reborn again one day.